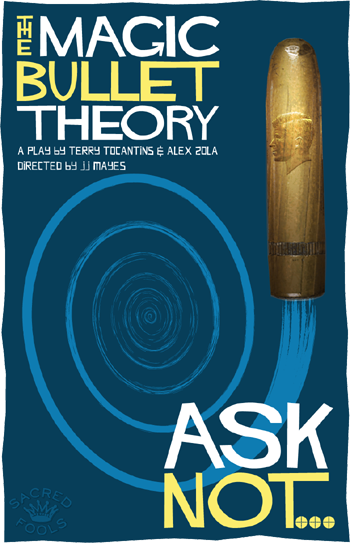

The Magic Bullet Theory

written by Terry Tocantins & Alex Zola

directed by JJ Mayes

WORLD PREMIERE!

MARCH 23 - APRIL 28, 2012

Fridays & Saturdays @ 8pm

plus Sunday, Apr. 15 @ 7pm

and Sunday Matinee, Apr. 22 @ 2pm

TICKETS: $20

(310) 281-8337 or Buy Tickets Online

Ask not...

November 22, 1963. America goes through the looking glass. The only thing anyone knows for sure is that someone murdered the President. Earl Warren had a take on it. So did Oliver Stone. Plenty of other kooks. Why can't we? Come and join our anti-hero Charlie Harrelson as he negotiates a trail littered with murder, betrayal, drugs, ghosts and yes, dear reader, Love.

Portions of an early draft of THE MAGIC BULLET THEORY originally appeared in serialized form in our late-night show, SERIAL KILLERS!

Reviews

"...not only wildly entertaining but leaves the audience with provocative and disturbing questions... a wild rompy but gut-laughy time." -Buzzine

"Directed by JJ Mayes with larky invention... satiric savagery..." -L.A. Times

"Imagine the JFK assassination replayed by Monty Python." -L.A. Weekly

Photos

No flash player!

It looks like you don't have flash player installed.

Click here to go to

Macromedia download page.

All photos by Amani/Wood Photography

Alternate postcard by David Van Wert

"No Excuse" poster by Mike McLafferty

Powered by Flash Gallery

Cast

Terry Tocantins as Charlie

Cj Merriman as Marsha

Rick Steadman as The Texan

Bryan Krasner as Louie / Whykowski

KJ Middlebrooks as Frank / Sanchez

Vanessa Stewart as Jackie

Eric Curtis Johnson as JFK

Michael Holmes as Lee Harvey Oswald

Marz Richards as Jack Ruby

Steve Hofvendahl as Chipmunk

Morry Schorr as Earl Warren

Victor Isaac as Arlen Specter

Lisa Anne Nicolai as Dorothy Kilgallen / Mary

Paul Byrne as Lee Bowers / Zapruder / Gov. Connolly / Doctor / Zangretti

Monica Greene as Yalie #1

Pete Caslavka as Yalie #2

Understudies

Marianne Davis, Dana DeRuyck, Isaac Nippert, Jessica Sherman & Brian Wallis

Crew

Lead Producer - Annette Fasone

Producers - JJ Mayes, Richard Levinson & Mike Schneider

Assistant Director - Suze Campagna

Stage Manager - Travis Snyder-Eaton

Choreographer - Natasha Norman

Assistant Choreographer - Matt Valle

Fight Choreographer - Andrew Amani

Set Designer - David Knutson

Lighting Designer - Yancey Dunham

Costume Designer - Jennifer Christina Smith

Prop Designer - Ruth Silveira

Sound Designer - Ben Rock

Original Music Compositions by - Michael Teoli

Graphic Designer - David Van Wert

Additional Graphics - Mike McLafferty

Feature Article

L.A. Stage Times

As its name suggests, Sacred Fools Theater specializes in irreverence. For

its late- night series Serial Killers, every Saturday night, audience

members see five short plays and kill off two. The three surviving plays return

the next week with new episodes. Last year’s critically acclaimed Watson started

off in Serial Killers, as did the company’s newest play The Magic

Bullet Theory, co-written by Terry Tocantins and Alex Zola and directed by

J.J. Mayes.

The Magic Bullet Theory, however, does not just treat murder as a

metaphor for what happens to the “killed off” plays in Serial Killers. It

takes off on perhaps the most dissected murder in American history — the

assassination of President Kennedy.

During an hour-long conversation before a weekday evening rehearsal, director

Mayes and co-writers Tocantins and Zola discuss their collaborations on The

Magic Bullet Theory — collaborations that they describe as integral to the

play’s development and final form. As the three talk about the play and sip

coffee in the theater’s dressing room, their gestures and sentences overlap.

Serial Killers host Tocantins and its co-producer Mayes emphasize that

the success of the series depends upon actors’ and directors’ willingness to

repeatedly fail in front of and seek inspiration from one another. This

willingness allowed them to transform The Magic Bullet Theory from a blog

post to a full-length play. They argue that the surreal dark comedy that

resulted from this collaboration more respectfully represents the assassination

than more linear narratives, such as Oliver Stone’s JFK.

From Blog to Stage

Playful experimentation has characterized Zola’s and Tocantins’ collaborations

since they met more than 20 years ago. As NYU students, they played together in

a band called White Noise. “Which pretty much described the sound we made,”

explains Zola, who started his writing career as a music critic for Spin. “We

didn’t have a drummer. We had a guy who played garbage cans.” Although their

latest collaboration does not have a garbage can percussionist, The Magic

Bullet Theory does include equally surprising elements, such as President

Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy crawling out of a television set to torture

Kennedy’s accidental assassin Charlie, played by Tocantins.

The play’s evolution has depended upon collaboration at every stage of its

development. It started off as installments for a novella that Zola posted on

his blog, The Zola System. When Tocantins read the posts, he thought they would

make great Serial Killers episodes. Neither of them had written a play,

but they pooled their talents as creative writer and actor to create two

episodes for Serial Killers, both of which Mayes directed. Although the

audience killed The Magic Bullet Theory after its second episode, several

company members encouraged the triad to turn it into a full-length play.

The first draft emerged from a two-day writing jam session between Tocantins and

Zola in Zola’s Phoenix apartment. Following advice from LA playwright Erik

Patterson, they pushed one another to “write about the thing that scares the

hell out of you.” Because they know each other well and enjoy challenging one

another, they could write quickly without censoring themselves.

The two also knew that their director would find and stage the play’s arc by

actively collaborating with them and with the cast and crew. Tocantins, from his

previous experience with Mayes, repeatedly remarks how he enjoys handing the

director challenges: “The fun thing about working with J.J. is that we can write

something surreal and kind of schizophrenic, and once we give it to him, when he

throws the actors on stage, he can turn that schizophrenic thing into something

that has its own loopy arc to it.” Tocantins and Mayes take turns recalling a

favorite moment from rehearsal when Mayes asked Marz Richards, who plays Jack

Ruby, to provide 30 more seconds of material:

Tocantins starts the story, “J.J. goes – dude, I need you to do something for 30

seconds between the chick exiting and then Charlie entering–”

Mayes interjects, “and it needs to demonstrate Jack Ruby’s temperament.”

Tocantins finishes the story, “And Marz Richards, this wonderful actor that we

have, boom, improvises four different scenes, in four different styles, four

different gags, all of them are brilliant, and it’s just about him yelling at

the bartender for slicing the limes the incorrect width. It’s something we would

never have come up with in the writer room.”

Mayes also hands puzzles like these to the crew. When faced with the problem of

how to stage a play with multiple settings and a character coming out of a

television screen, he gave set designer David Knutson a single word to guide him

– “gears.” Knutson returned four days later with seven different designs.

Accidental Tragedy

This collaboration has yielded a surreal dark comedy that explores the chaos

wrought by the Kennedy assassination as well as the accidental nature of life.

Zola points to Terry Southern’s Dr. Strangelove as their model: “I would like to

think that we did to the Kennedy assassination what Terry Southern did to

nuclear war with Dr. Strangelove.” Mayes emphasizes that the play’s surreal

spectacles, such as its dream ballet, all serve a purpose. The closing musical

number, for instance, illustrates the internal confusion experienced by Charlie

before he shoots a judge:

“It’s a giant spectacle, but it’s not that we just needed a song and dance — how

do we demonstrate how much crazy stuff is going on in his head? How do you do

that on a stage and make it interesting and not make it us telling you that? You

take every character in the play and you blow out a giant musical number that

uses every inch of the theater, and then you shrink it all back and fire a shot.

So the spectacle is what allows us to move the narrative.”

The play’s surrealism not only represents the killer’s internal confusion but

also the chaos that engulfed the nation after the assassination. Mayes recounts

the responses to the play from two company members, who were alive during and

remember Kennedy’s assassination, in order to illustrate the experience that he

thinks the play provides:

“When we did one of our first readings, Ruth Silveira and Leon Russom, who

remember the assassination, they were like — ‘what’s really wonderful is that

this isn’t telling the story of the assassination so much as it’s describing how

it felt to live through it. This is what happens to the American public. This is

what it felt like — this kind of chaos and confusion, not knowing where to look

or who to look to, not knowing how to tell the story or not knowing how you

feel, the chaos that you felt within but couldn’t describe.That’s why the show

works’.”

For Tocantins, the transformation that the assassination wrought requires this

surreal approach: “It was a vortex and any kind of vortex is going to be

out-of-this-world surreal. We did go through a looking glass; we’re trying to

earn the surrealism with some sort of moral center, because there was an act of

violence and the consequences were never fairly doled out.” In The Magic

Bullet Theory, this vortex results from a series of accidents rather than an

organized plot to kill President Kennedy.

For this director-writer team, imagining that a series of accidents led to

President Kennedy’s assassination points to the source of life’s real tragedies.

Tocantins explains that although people love stories about premeditated and

well-orchestrated plots to kill the president, these stories hide the real

tragedy: “Life is accidental and chaotic. People fall out of love with you and

they leave and they leave you alone and you take drugs and then you’re supposed

to do a prank and you end up killing a man — that’s the tragedy. This particular

character killed a president because his love life was upside down.”

Mayes argues that the play illustrates how small accidents can build into

disasters — a process that he believes audience members will recognize from

their own lives.

The three men’s goal for the play parallels how Mayes describes Sacred Fools

Theater’s ethos. They hope the play strips away audience members’ existing

stories about the assassination and allows them to feel the human tragedy of

Kennedy’s murder. The company similarly expects its members to leave their egos

outside the theater so they can interact openly with one another and with the

dramatic material.

To illustrate this, Mayes tells a story about an experienced company member’s

response to a new member’s bragging. He took the newcomer out to the sidewalk

and said, “Out here you can talk about anything you’ve done. In there, you’re

just another fool. That’s the mentality that exists here. There’s nobody above

doing anything. Amazing things get created here that I don’t think can exist

other places.”

--Alison M. Hills

© 2012 L.A. Stage Times

Reviews

Buzzine

Theories about the Kennedy assassination have been explored in film and stage

many times, but not like this mad romp and wild chaotic ride at Sacred Fools --

L.A.’s delightfully irreverent theatre company.

The Magic Bullet Theory suggests that a muddle-headed, love-impaired

assassin was hired not to kill but to miss his target with a warning shot…and he

messed it up and accidentally killed the president. Absurd? No more absurd than

the decision reached by the Warren Commission: that there was only one shooter

-- a demented guy named Lee Harvey Oswald, and that the bullet went in one

direction, deflected off a bone, changed direction, and hit another target. And

since the story is told in music, in dance, in a romp of improbable scenes

filled with crazy government guys, crazy mafia guys, with an absolutely

side-splitting pantomime of “tragedy” using slow-motion, I asked the authors if

they intended this to be Theater of the Absurd.

Note: Theater of the Absurd was a movement in the '60s where “absurd” plots and

unreal irrational scenes somehow leave the audience with a “message” -- a clear

concept sometimes more effective than conventional theater. For instance: No

Exit, by Samuel Beckett, where a character carries a heavy suitcase full of

sand and refuses to put it down: a powerful life lesson. Or The Sandbox,

by Albee, where the old granny is kept in a sandbox with her very own food dish.

Or Krapps Last Tape -- a powerful play where an old man sits monkey-like

eating a banana, listening to the tape of his brilliant youthful ideas.

This play was conceived at Sacred Fools’ Sunday night competition called Serial

Killers, where short segments of new plays are “voted on” by audiences, and some

of them developed into full-length plays. This was one conceived by Terry

Tocantins and Alex Zola. Zola, one of the authors, said he couldn’t quite call

it “absurd theater.” He wanted to approach the Kennedy assassination in the same

way that the atomic bomb was portrayed in Dr. Strangelove. Yet, their

“absurd” view of a horrendous event is not only wildly entertaining but leaves

the audience with provocative and disturbing questions.

The major shocker after the laughter dies down: 169 people involved in the

assassination have died since the event. 169. And in many scenes, a drunken

Dorothy Kilgallen pratfalls and is dragged out. I had to Google Dorothy

Kilgallen, who was, to me, vaguely familiar as a news commentator of that

period. Dorothy Kilgallen claimed that she knew who killed Kennedy, she was

about to reveal it, and she died suddenly and mysteriously. The “play” runs an

hour 45 minutes without intermission. But the action is so entertaining, often

so puzzling, that I spent the first half not only laughing but trying to

reconcile the plot with what I remembered of the real event, and the second half

thinking, "Oh, who gives a damn?" and just letting go and having a wild rompy

but gut-laughy time.

Vanessa Stewart plays Jackie, wandering through the action in her familiar

pill-box hat and blood-spattered skirt. Michael Holmes is a scattered, rather

idiotic Lee Harvey Oswald. Terry Tocantins, with his gun handy, is the guy who

shot and should have missed, but hey, it was an off day. And the wonderful

two-guy schtick which demonstrates faces of “tragedy” was done in “slow- motion”

by Bryan Krasner (who plays remarkably like the iconic Zero Mostel) and K.J.

Middlebrooks. Jack Ruby was an effective Marz Richards. I saw the play opening

night. It still needs a bit of cutting, tightening, and shaping, but even as is,

just a great night of fun with a bonus of a lot of afterthought…which makes for

a successful night of theater.

Plays like this one, and indeed the name Sacred Fools itself, provoke deep and

disturbing questions. Our great democratic society was created out of a wild

experimental shakeup of old entrenched chain-of-being ideas, challenging the

sacred rights of kings to rule the lives of the rest of us. Democracy in theory.

Yet today there are, as one of our great playwrights tells us in the play of the

same name: “…little foxes that spoil our vines…and eat our tender grapes.”

Mayors use their communities for personal profit. Our politics have always been

ripe subject for comedians, but this year’s election doesn’t even need a

comedian to interpret the madness of the season.

We live in this great chummy Internet community without knowing if all our

personal information is being used for commercial or nefarious reasons. We have

little idea of why our wars are being fought, and we still don’t know what

powerful figures are trying to buy our elections. And somebody (or some

organization) kills one of our great presidents, and with all our resources, we

still don’t know the truth of who-dunnit? Serious theater has always been in the

front line of inquiry, challenging us to think critically and act “morally” in

the best sense. Today, theater may lean toward “entertainment,” but there is

still a challenging and provocative theater to question the “system.” They still

reprise Death of a Salesman with its moral central issue, and the

“absurd” Waiting for Godot is currently playing on Broadway. It’s for

innovative and provocative and perhaps “absurd” theater to challenge us to think

and act. As the character says in Godot, “I can’t go on, I must go on, I go on.”

So more courage to experimental theaters like Sacred Fools and their wild

improbable humor to keep alive unsolved mysteries like the incredible cover-up

of the assassination of a great president.

--Clare Elfman

© 2012 Buzzine

L.A. Times

An intriguing notion shoots through the ricocheting subversive brio of "The

Magic Bullet Theory." By training their thematic sights on a surprisingly

credible conceit -- that John F. Kennedy's assassination was the unintended

result of a bungled scare tactic -- playwrights Terry Tocantins and Alex Zola

give this irreverent Sacred Fools presentation noteworthy substance.

Directed by JJ Mayes with larky invention, "Bullet" follows Charlie Harrelson (Tocantins,

effectively restrained), the real-life convicted killer of Judge John H. Wood

Jr., and father of actor Woody Harrelson.

Sandwiched between an incredulous Earl Warren (Morry Schorr) and the archetypal

Texan (a rip-roaring Rick Steadman), who facilitated things before and after

Nov. 22, 1963, Charlie carries the ironic tangent: he, Lee Harvey Oswald

(Michael Holmes) and two CIA-recruited Yalies (Monica Greene and Pete Caslavka)

were supposed to "miss the target." Oops.

What recommends "Bullet" is the garage-show confidence with which Mayes,

choreographer Natasha Norman, the design team and a laudable ensemble attack the

mayhem.

Ever-smiling JFK (Eric Curtis Johnson) and torch-singing Jackie (the redoubtable

Vanessa Stewart) lead gonzo dance breaks. Mafia goombas Louie and Frank (Bryan

Krasner and K.J. Middlebrooks, hilarious) witness the botched job in Mascagni-accompanied

slow-mo. Dorothy Kilgallen (Lisa Anne Nicolai) proves harder to dispatch than

Rasputin; Arlen Specter (Victor Isaac) charts the title equation in a

red-threaded absurdist snarl.

Things go sluggish by the two-thirds point, needing either an intermission or 15

fewer minutes of repeated shtick and false endings. And Charlie's back story

with impregnated Marsha (Cj Merriman) misses the anarchistic mark, prosaic and

gravely histrionic amid the satiric savagery that otherwise denotes "Bullet" as

a representative company melee.

--David C. Nichols

© 2012 L.A. Times

L.A. Weekly

Terry Tocantins and Alex Zola's The Magic Bullet Theory, closing this weekend at Sacred Fools Theater Company in Hollywood, is the second play to be produced locally this year focusing on the 1963 JFK assassination.

Dennis Richard's Oswald: The Actual Interrogation was performed in January and February at Write-Act Repertory, also in Hollywood. Though strategically ambiguous, Richmond Shepard's staging of Richard's play appeared at least in part to support the lone-gunman theory (the conclusion drawn by the Warren Commission): that a single ricocheting bullet (from one of three shots) killed the president of the United States and wounded Texas Gov. John Connally, both of whom were riding in the sedan with their wives as part of a parade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963.

With the exception of a couple of flashbacks, Oswald arrived at its view through an extended interrogation scene between the accused Lee Harvey Oswald and a mild-mannered Dallas Police Department captain, Will Fritz — a scene cobbled together from Fritz's hand-scribbled notes. That production also posited the suggestion that Oswald had been framed.

The tone of that production combined the noir melodrama of Dragnet and Law and Order, honoring the almost theological conviction of baby boomers that those three shots heard around the world in November 1963 represented the beginning of the end of innocence for the United States.

The Magic Bullet Theory, however, written and produced by post–baby boomers, defies all such reverence, and with that defiance carries a healthy skepticism that any era of American history, or any other history for that matter, was innocent. Its larger point is its derision for the controversial single- or "magic" bullet theory.

As directed by JJ Mayes, it presents a sketch-comedy conspiracy, irreverently choreographed by Natasha Norman, that unambiguously leaves the Warren Commission report in tatters. In fact, one scene dramatizes the single-bullet theory with an actor holding a bullet, which carries a tail of red string, from the assassin's rifle to and through the passengers (actors posing dutifully in a cardboard cutout of the open sedan). The scene demonstrates the trajectory of the bullet, which would have almost had to reverse directions in midair to support the single-bullet theory, in the meantime slicing through 15 layers of clothing, about 15 inches of tissue and a necktie knot, taking out a chunk of rib and shattering a radius bone. (This point of view also could be found in Oliver Stone's movie JFK as well as its parody on Seinfeld.)

The play replaces that theory with a highly speculative suggestion that the assassination was a botched conspiracy, headed by The Texan (Rick Steadman) — Lyndon Baines Johnson goes unnamed — employing a couple of "Yale-Fuck" killers (Pete Caslavka and Monica Greene), as well as Oswald (Michael Holmes), plus Charles Harrelson (Tocantins), who, with Oswald by his side, fires shots before placing the murdering rifle into dimwit Oswald's hands, thereby also supporting the notion that Oswald was framed.

Life may be stranger than fiction, but this fiction hangs on the most tenuous of threads: that the Texas contingent and the CIA were so peeved by President Kennedy's soft handling of Cuba, they just wanted to scare him, to let him know what they could do if he didn't stand up to Castro. In flashback, we see The Texan order the parade slowed to 10 miles an hour so the hired guns could fire and miss, sending a message, Mafia-style. But something went terribly, terribly wrong.

Imagine the JFK assassination replayed by Monty Python. The Brit sketch-comedy troupe infuriated millions of Catholics with its version of the Crucifixion in Life of Brian. (The crowd whistles to the lyric "Always look on the bright side of life" as the Savior hangs and nods in rhythm.) The Magic Bullet Theory is a comparatively local sacrilege — a couple of thugs dance in slo-mo, mock anguish whenever they see somebody killed. The production dances gleefully with nihilism, finding its footing somewhere between bravery and childishness.

--Steven Leigh Morris

© 2012 L.A. Weekly

Fridays & Saturdays @ 8pm

Sunday, 4/15 @ 7pm

Sunday Matinee, 4/22 @ 2pm

Tickets: $20

BUY TICKETS NOW

& Alex Zola

CJ Merriman as Marsha

Rick Steadman as The Texan

Vanessa Stewart as Jackie

Eric Curtis Johnson as JFK

Michael Holmes as Lee Harvey Oswald

Marz Richards as Jack Ruby

Moory Schoor as Earl Warren

Victor Isaac as Arlen Specter

Lisa Anne Nicolai as Dorothy Kilgallen

See the full cast